Petar Janjatovic: The music encyclopedia from Lion

As a kid he would hang off of tramways and would sneak into the movies - then he fell in love with music. Still, it wasn’t instruments that became his weapons, but rather the written word. Travelling to almost every corner of the world, he reported from concerts, did interviews with bands both famous and soon to become that way and in the process heavily influenced the domestic rock scene. Petar Janjatovic, journalist, music critic, writer and a true music encyclopedia from Lion speaks for 011info about his growing up, moments of his life and explains the way a hippie feels today.

What were your earliest childhood memories?

They have to do with the part of the city between Lion and Red Cross where I grew up. My street was a quiet one with not much traffic and it was there, in a certain square, that we all gathered. Always like a pack. When I look back on those times from today’s perspective, I feel as though I grew up in a small town somewhere, where the same locals hang out every night.

The “Beograd” cinema garden was nearby. We all of course loved movies so we would often sneak into the movies without a ticket by going through surrounding yards. The entire summer cinema was like some kind of seaside location. Today, that garden is abandoned. Luckily it wasn’t torn down because of some rare trees that were planted there, so it’s like a miniature botanical garden.

Similarly, in the corner of Gvozdiceva and Revolucije boulevard, there was the tavern “Lipov lad” that had stood there since WWII, before it was torn down in 1974-75. and a new one was built there. Seeing how the Boulevard was packed with tiny craft workshops and stores, we all knew which tables were usually taken by bakers, mechanics, shoemakers...this was where our parents took us to treat us to cevaps when we got good grades in school. When the tavern was torn down, my twin brother Rasa brought their huge, handwritten menu (with prices) that used to hang on the tavern wall for years - it was yellowed from tobacco and grease. Sadly we didn’t keep it, I would’ve loved to have it today.

Later, whenever they asked me where I lived, I’d tell them “Near that tavern where Dragan Nikolic auditioned to sing”.

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

What was it like growing up in those days?

We were typical kids who chased the ball around with scraped knees. Our playgrounds were the foundations of today’s red skyscrapers in Vranjska street and we’d usually go back home covered in dirt. You could say it was a typical small-town childhood.

Then the gradual conquering of Belgrade came. Back then we had the tramways we called “Belgians” and our main entertainment was latching onto them and riding from Lion all the way to St. Mark’s church. From there, we’d go on to get into shenanigans. It was dangerous and some people lost their lives doing it, but we felt like action heroes. It was insane and exciting. Older generations say that cops would wack them with their batons on the rear a few times for that kind of stuff. I’m younger so I never had that happen.

While growing up, you also became a huge fan of taverns

My father Dusko worked as supply chief for the “Majestic” hotel. When he’d bring Rasa and me to work, it was a party through and through. We’d rush over to the confectionery part of the kitchen where aunties who work there would sit us down and give us tons of sweets.

By the end of the 60’s, Majestic was highly reputable and they had some products in their offer that were unheard of until then. For example, it was in their huge refrigerator that was the size of an entire room, that we saw cans of Coca-Cola and Schweppes for the first time. Imagine the experience of sitting there, sipping something from a can that half of your city had never seen before. That’s how my relationship with taverns was born.

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Do we have ‘taverns’ in that same sense today?

Belgrade does have godo taverns with that old-town charm. I know of five or six of them and I frequent them to scratch that itch. A good tavern revolves around food and drinks, but the key is laughter. They have to be filled with laughter. I love tavern noise - everyone is always shouting when they’re arguing or celebrating.

I believe that every other waiter has a sense of humor. Around the late 80’s, I knew the ambassador of Britain from back then who was a huge fan of taverns. I took him around such terrible dumps that you wouldn’t believe. It was in one such dumpy tavern that we encountered ‘brizle’. I had no idea what those were, so I asked the waiter to explain. He grabbed his throat, making choking noises and said “Those are some glands that cows have around here”. That was when I coined the phrase stand-up waiter.

When did your love of music start?

Ever since I was a child, maybe 5th or 6th grade in junior school. We were fanatical about listening to the radio because it was the fastest way to get information. We’d always drag around a transistor. Alongside movies, rock n roll was the most entertaining creative activity of the time. It was the period when the Beatles were at their peak and the so-called hippie generation was born. It made sense for a young person to be drawn in and caught up in that.

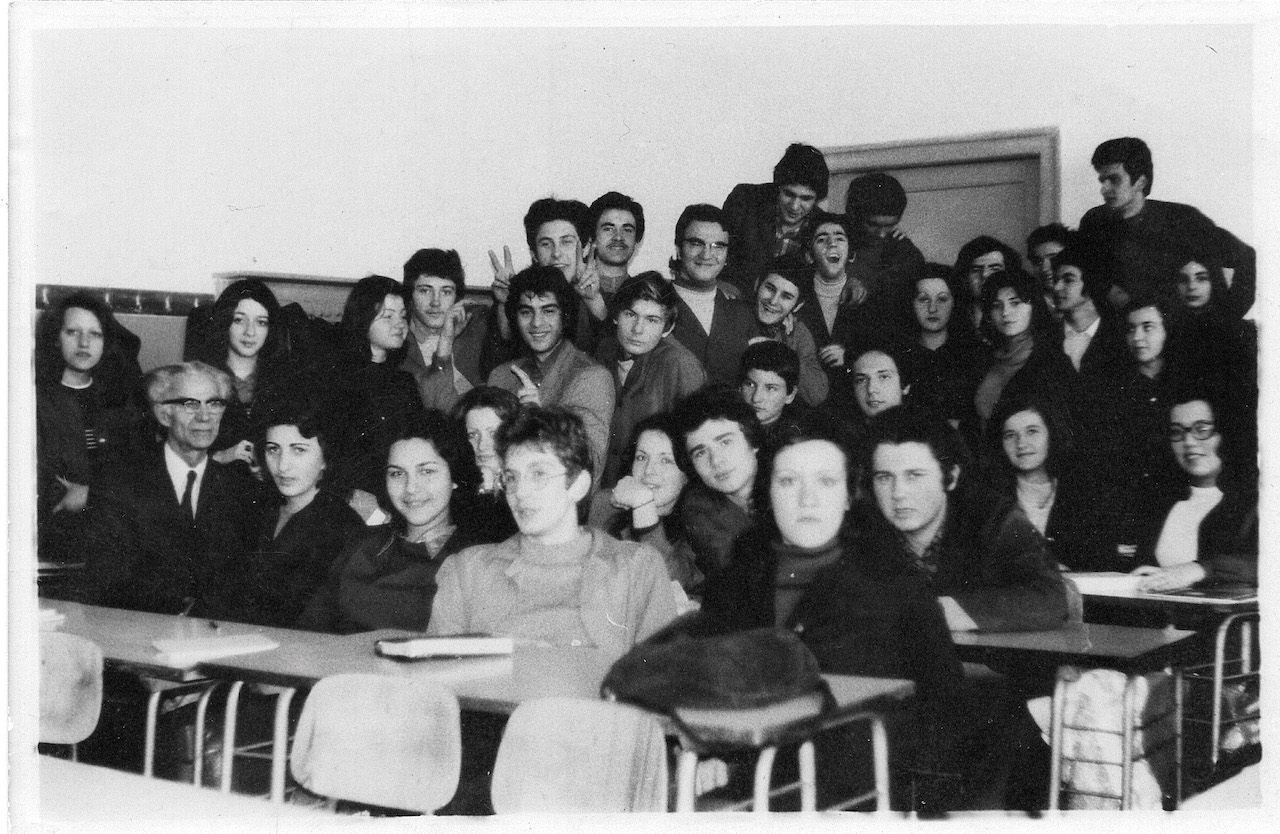

Photo: Z. Živković / Private archive

In addition to all of that, you were also drawn to books and writing.

Both of my parents loved the written word. My mother studied literature and our house was full of books, so we grew up surrounded by them. Also, my uncle worked as the editor in “Nolit” and kept bringing us new books all the time. We’ve had guests come over and look around our house in amazement, at the overflowing shelves, asking us “Did you really read all these books?”

From time to time, our mother would take us to an antique shop near Beogradjanka, where we were allowed to buy two books each and we looked forward to that ritual a lot.

My father passed away suddenly at the age of 61, but a few years prior to that he got the idea that he could tell me his life story so I could turn it into a book. We kept putting it away for another day, but that day never came. I regret that a lot.

And then you brought your two big loves together.

Seeing how I wasn’t that talented for playing and singing, but I loved music, it was great for me to write about it. At first, I wrote about all sorts of things - books, movies, I created report articles, travelling articles - I had no idea I’d end up as a music journalist.

In the late 70’s and early 80’s, the newspaper “Zum reporter” was popular and it was like a poor-man’s version of Zagreb’s “Start” magazine. It had pornography, interesting articles and expansive interviews. It was for them that I wrote about the last remaining workshops that made soda-water in Kalenic and little hidden corners of Belgrade that I unearthed.

As the new wave came, I got the opportunity to work in “Studio B” and “202”, to write for “Dzuboks” and various other newspapers. I was more and more consumed by music and at one point I realized that was all I wrote about. It was spontaneous, no thought involved.

Why? Because that was the most fun. Of course it was nice to write about movies and interview actors and writers, but this was a non-stop party.

In addition to being fun, it was also very easy to sell those articles. There were plenty of media. I could write non-stop.

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

With a few other colleagues like Peca Pejovic it was you, personally, that gave rise to this form of journalism. Was it a fun experience?

We had excellent journalists. In Zagreb, we had Darko Glavan and Drazen Vrdoljak, they were the pioneers of the trade. In Novi Sad, we also have a few colleagues born in the early 50’s who were pioneers as well.

For example in “Dzuboks”, we had a section called “On the road”. We’d travel with the bands to their gigs, usually in smaller towns, and write about the happenings on the road, encounters with fans and all the little mishaps and such. That was how one winter our friend Buca Popovic accompanied “Idoli” on their gig in some firefighting station in some god-forsaken little place in Vojvodina. It was a total disaster. The audience demanded they play “Motori” from the band “Divlje jagode” which they refused. It cost them a set of slashed tires on their van. On top of that all the organizer prepared for their food was bologna and bread. Can you imagine the legendary “Idoli”, all dressed up and sitting in some dinky office, eating bologna?

I renewed that section when I worked for the “Rok” magazine by writing a juicy report on “KUD Idijoti”. I drove them to a ‘no budget’ gig in Smederevska Palanka. It was also Tusta’s birthday so they made him a cake. It was just shenanigans from start to finish and very fun to write.

The proof that journalism can be interesting is also the experience of my friend and musical journalist Dragan Kremer. Around the mid 80’s, he began to write about folk music the same way as he’d write rock’n’roll criticism - about song authorship, production and the like. Among other things, the then indomitable “Politika” newspaper published his review of the first Toma Zdravkovic concert in “Dom sindikata” when he returned from America. Months later, he found out that Toma was looking for him to invite him to the promotion of his new album because “no one else had ever written something like that about him”. After the big promotion at “Majestic”, in the afternoon the inner circle sat down for some drinks and conversation. After the restaurant closed down, they moved to the legendary suite at the top of the building and throughout the night various people came and went. Toma introduced every single one of them and the next morning we were also visited by ‘ladies of the night’ who were off their shift. Toma truly respected them all, so he ordered breakfast and coffee therapy and we only parted ways when he had to go attend a previously scheduled TV appearance. To this day it’s one of Kremer’s favorite experiences of his career.

Was this a better time for music, journalism and life experience in general than today?

It was certainly better for journalism because we had good, strong media. We had massive newspapers that could send you on a trip and cover all the fieldwork expenses. Yugoslavia had a unique position so we got special treatment around the world.

For example, in Paris, in July 1982, I saw a poster for a “Talking heads” concert which they had scheduled in Belgrade a few weeks later. I asked a friend of mine who spoke perfect English to call the organizers from the poster so they would host us as journalists at the concert. Much to her astonishment, she was told that passes were already waiting for us at the entrance. The concert was amazing, everything was excellent, but…

When I went back to Belgrade, I told Branko Vukojevic, then the editor of “Dzuboks” all about it and I showed him the laminated pass they gave me. He took one look, turned it around and asked “What was the aftershow party like?”

I gave him a blank look, like ‘I don’t understand’. He shows me the back of the pass “It says aftershow right here, you were invited to the aftershow party”. Back then I had no idea what ‘aftershow’ meant, I’d only heard about ‘aftershave’ (laughter).

The point I’m trying to make is, you could see a phone number somewhere, dial it, introduce yourself as a journalist from Yugoslavia and the door would open for you. So, it was really, really better. Today, if you told someone you were a journalist from Serbia, what do you think would happen?

When it comes to bands, it was easier for them back then because there was a lot less music being recorded. Punk and the new wave brought never before seen themes to rockenroll. So it was this huge unexplored field. It’s hard nowadays for musicians to be original, so it’s no wonder there’s a lot of covers going on.

On the other hand, you’ve got “Artan Lili” which is a very interesting band and they have their own color. You have these kids from “Butch Cassidy” who played in Zagreb five times in a row. They speak to their confused peers and this covers some very good ground and comes in an interesting package. When you have a strong handwriting, it’s all much easier. Then, even themes that were covered before can be given a new spin.

There’s a similar situation in literature too. Maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t see newer generations reading the classics. Although there are kids who are curious and will read James Joyce without problems.

What I mean to say, most of the reader audience is looking at books that last for a month. And the music no longer has the impact it had before. Today it’s all Silvana to Nirvana.

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

How can music critique impact that?

I’m afraid that music critique has no impact at all. Due to the insanity that is the internet, it’s hard to attain readers. Masimo Savic recently talked about the time when everyone lived in trepidation from critiques by Dragan Kremer and Pera Janjatovic when a new album or concert came out - although we had no idea nor did we see ourselves that way.

The only place where I can see a role for critique is guidance in this forest of music. If you have someone whose taste in music you trust, you should follow their advice. For example, I like to read movie critiques by Milan Vlajcic. I trust him and I watch movies that he praised while skipping those he disliked. I generally feel that art critique is in crisis.

On occasion I write for “Vreme”. Sometimes a column will come out and nobody will mention reading it. But whenever I appear on TV, my phone catches fire. It’s just that the media has focused on television and internet.

On the other hand, there isn’t a TV show that seriously deals with culture like we used to have. Back in the day, we had the show “Fridays at 22” which covered all the creative fields and the entire Yugoslavia watched it. Back then, it was enough for a performer to have an interview with, for example, “Rock” magazine and appear on “Hit of the month” and they’d be set. Nowadays you have to bend over backwards to be visible, which shows the poor influence of media.

Your musical encyclopedia is a very unique and significant work for domestic music. You’ve written it based on your own experiences and in such a tone that it’s a pleasure to read.

My entire goal was to make it interesting to read, so that anyone who wishes to make a scenario for a rocknroll movie can find a bunch of scenes, situations and events in the book that can be the binding tissue.

I was aware that the book would provoke my colleagues and many would be pulling out their hair that they didn’t write it, but I beat them. Luckily, it just so happened that Bogica Mijatovic wrote the encyclopedia of music from Novi Sad and Vojvodina, while another colleague wrote the encyclopedia of Zajecar rocknroll. So now every major city has its own encyclopedia.

For example, around a year earlier the “Encyclopedia of Croatian millenium rocknroll” came out. It was interesting to read because it had a lot of information I didn’t know.

From the very first edition, many of your fellow journalists held it against you that you didn’t include all genres of music, more specifically metal. Why? How popular was metal music among journalists?

Only our journalist Jadranka Novakovic who was a metal heroine and adored by her audience listened to it. She was almost a bigger star than some musicians.

The decision to not include metal was my own personal disregard. I didn’t want to write about a genre of music that I personally didn’t appreciate. So I only included some of the most representative names from heavy metal such as “Pomorandza” from Slovenija, “Divlje jagode”, “Griva” and some others.

I didn’t dabble too much because let’s be realistic, it’s boring to write about metal.

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Were you ever a target of threats as a journalist?

No. When I gave out a harsh critique, people would turn up their noses at me and not talk to me for years at a time. Once they got over it, we’d continue communicating. They’d also get angry if I refused to write about their albums if I deemed it too poor and thought it was best not to.

I think that we music critics are really just affirmators for music. We should deal more with music that we think is high quality, rather than what we don’t like, unless that lame music hasn’t become too toxic.

So I was mostly left alone, unlike Kremer whom we mentioned earlier. He had people come to his home to threaten him. I didn’t have that kind of reputation. I was more of a “flower power, peace, love” kind of person!

How (un)comfortable are times nowadays for hippics?

It’s ghastly. The negative utopias we read in the 70’s and 80’s have come to life several times worse than George Orvell could’ve dreamed. The entire world became very selfish and there’s a tremendous amount of disregard and hatred everywhere.

I used to hitchhike all around Europe for five or six years straight. I could spend up to a month on the road. I never had an unpleasant experience. All sorts of people picked me up: pensioners, truckers, businessmen, entire families…

For example, in France my brother and I were picked up by a young couple with a five years old daughter. We sat in the back with her while she taught us the lyrics of a French song that won Eurovision that year. She was in tears when we had to part ways after seven hours of riding and asked us to keep traveling with them.

From today’s perspective, would you have ever picked up two dishevelled, bearded, dusty idiots on the road? And let your child sit with them? We had trust back then, and good judging of character.

Could you tell us about a song that’s underrated or it never became a hit even though it deserved to be?

“Yu grupa” has a song from their first album called “Noc je moja” which was popular for a few years when the album came out and then it went away. They don’t play it in their concerts anymore and I think it’s a phenomenal song.

If we’re talking about Yugoslavia, Franci Blaskovic and his wife Arinka have a band “Gori Ussi Winnetou”. In the year ‘93-94, in the middle of the war, he covered the old Istar song “Tri nonice”, but gave it a physical connotation about nationalistic hatred. Great song! I used to play it on the radio when I was with B92. I wish those two were a bit longer-lived.

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Was there a concert you regret never attending?

Of course, hundreds of them. One in particular I can’t get over was “Suboticki festival” in 1980. The Festival was moved to fall because of Tito’s death. I don’t know why I wasn’t there, but the bands “Film”, “Haustor”, “Idoli”, “Sarlo”, “Orgazam” were all competing that year. Everyone made a name for themselves that year - imagine four days with that crazy crew!

Kremer was on the scene and he told me that he and a photo-reporter from “Dzuboks” carried Jura Stublic out of a tavern dead drunk. As they dragged him to the hotel by the armpits, he’d kick rearview mirrors off of the cars they passed. If I were there, I could’ve gotten his legs and stopped him from doing it.

Anyway, that was an important festival.

To what extent have festivals nowadays consumed certain performers?

They’ve helped them as much as they’ve consumed them. Take for example Rambo Amadeus’ performance in “Exit”. He’d never get to play in front of 30.000 people if not for “Exit”.

The Pandemic aside, those festivals are very important economically as well. They allow the bands to perform in more gigs.

Our problem is that a significant part of the younger audiences don’t have the habit of going to concerts and listening to songs. Tribute bands ruined a lot of that because they’re always playing someone else’s encores. Then the young music consumer has no patience to listen to a performance if the hits don’t come until the very end. It all boils down to “I want it all now”.

One of the things I think survived are small clubs. Like “Kvaka 22” in Cetinjska. There’s always been a small crowd that gathered there to follow new bands. For example, back during the new wave, they had three new demo bands play every Monday in Dadovo which can only house 200 people. I saw the first “Partibreakers” concert right there. We went to keep up with the new names and spend time together.

The entire Belgrade punk scene was centered in the lower SKC club that could only take in 300 people, and Belgrade has over a million residents. It was never a huge, massive thing. It all became massive because of the festivals.

On the other hand, you have “Beer Fest” where people go to drink and don’t care who’s playing. They don’t even notice who’s on the stage. You can’t even spectate in peace because of all the commotion.

There’s two sides to everything, of course.

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

Photo: Vojislav Vujanić

In addition to preparing the fifth edition of “Ex YU rock encyclopedia”, what are your plans for the future?

I’m getting ready for retirement - at least in age.

I don’t dare to make plans too much, mostly due to how busy I am with the record company. However, I like the idea of talking my friends into writing books and then editing for them. I did that with Voja Pantelic and his jazz interveiws that we did in the book “Jazz face”. I also edited the autobiography “Wrinkled thoughts” for Branko Golubovic Golub from Goblin. It did really well too with fans. I keep thinking about books where I’d be the crowning touch. Seeing how I’m not sure I could write a whole something. Although I did get motivated when I read Rajko Grlic’s “Untold stories”. Which I warmly recommend by the way. In that book he alphabetically listed terms from cinematography and wrote about various things from his life related to them. When I met him, I asked his permission to ‘steal’ this concept from him and got the green light. There are so many untold stories, but my problem is making the right format for that book so that it’s not just a line of anecdotes.

You said that you used to write about various side-streets of Belgrade. Are you maybe considering something like that?

It’s been a year or so that I’ve been writing a column for a Slovenian newspaper called “Postcard from the capital” where I write about everything but music. I send a report from Belgrade to an imaginary Slovenian audience. I write about taverns, domestic political mishaps, anecdotes and such. It keeps me warmed up. I haven’t thought about it, though. But I could probably also put those kinds of stories in the book I mentioned. I thought about naming it something like “Wandering”. That was the title of my travel and sex stories I wrote in the late 80’s for the Novi Sad newspaper “Stav”.

You know what, there are so many excellent writers that I don’t feel like writing. When you start reading their stuff, you realize you have nothing to hope for in that lane. I don’t have false modesty, but there are simply people who say what they need to say in three sentences where I’d need seven. I’m comforted by the fact that there are also those who can take my seven and make them into seventy!

6 ℃

6 ℃