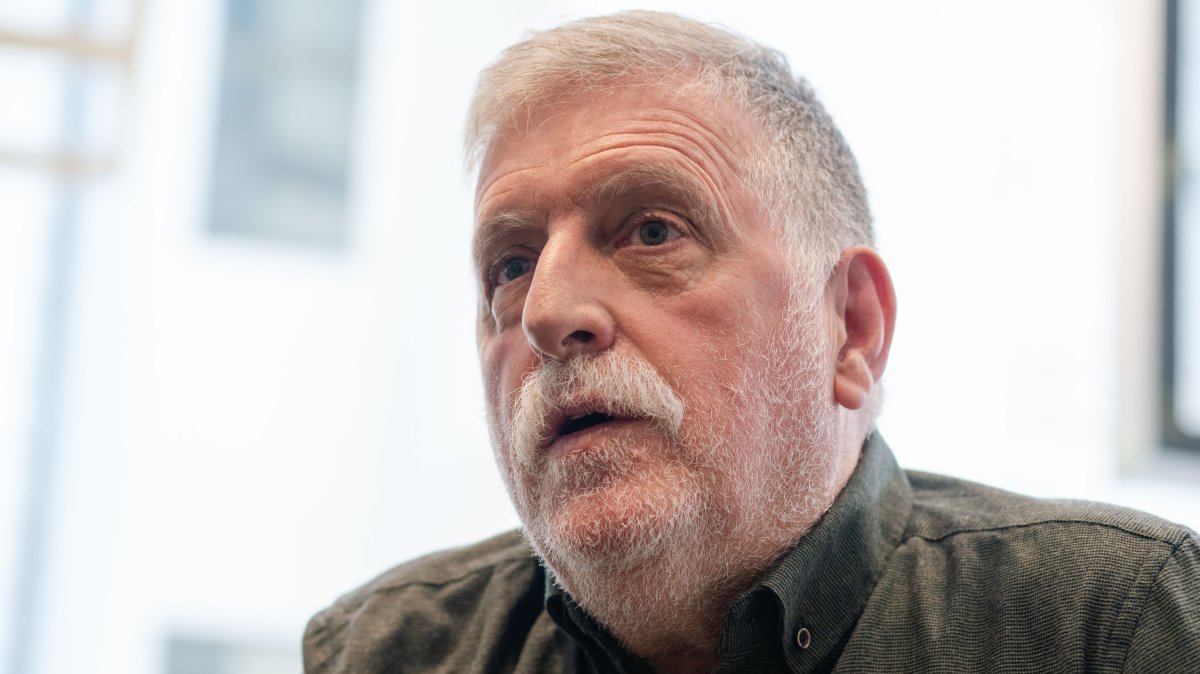

Peca Popovic: a rock fan whose heart is full of Belgrade spirit

Petar Peca Popovic has an impressive career behind him. His name is synonymous with the titles of music critic, rock historian, "Jukebox", "Rock" and we can freely say that he was the one thread that weaves through the entire ex-YU rock scene.

Peca Popovic talks with 011info about the Belgrade he grew up in and the spirit of a city that shaped him in a specific way and gave a special tone to his life.

How do you remember the Belgrade of your childhood?

This Belgrade isn't that Belgrade which means that this Belgrade doesn't have what we had back in the day. You know, any trip down the memory lane makes you introspect and see if you grew up in the way that the Belgrade of your childhood deserved.

I personally think I did age the way that Belgrade deserved. That means never stop running with the pack and keeping close the values you picked up growing up, never forgetting the people who taught you, who brought you into the city, into literacy, education, some beauty you wanted to get close to.

This Belgrade of my growing up made you open your heart and travel the world and still see why you'd never leave Belgrade for anything you could see abroad. What did this miracle have that all those other locations didn't?

And when you think about it a bit better, everything you picked up growing up still stands today. The one who doesn't love their city and their family and first address, doesn't love anyone. I firmly believe that.

What is it that sets our capital apart from others in your opinion?

Today we can find a million flaws in Belgrade, but there is one thing that nobody can take away from this city, which is its spirit - no matter which political party is in power. You can have any amount of power, but you can't destroy the thing that sets it apart from others. It's the foundation built by the great guardians of Belgrade, the people - rather than the government, party or ideologies.

There is a Turkish proverb that says "Get away from the two-river city". But Belgrade isn't a city on top of two rivers, it sits atop four. It has Danube, as the most important European river, Sava as the most important Yugoslavian river, its own authentic Topciderka and the biggest river of west Serbia - Kolubara. All these four waters run towards the same goal, but they pass through the filter of Belgrade and each of them carries something. One carries Europe, the other our region, the third Serbia and the fourth Belgrade itself and all of them symbolically come together under the Victor who stands with his back to the Balkans and looking out to Europe.

When you know you left a certain environment you have to be aware you can't embarrass yourself by accepting values that aren't typical for Belgrade.

The biggest 'bad-boys' of Belgrade - and by that I mean people with big hearts who didn't care about gain, but how to defend the city spirit and never did it for the glory. It was important to them to be able to do something that doesn't embarrass the city and make it remember them. To write a single lyric or a sentence, to make a move on the soccer or basketball court, to build a cabin on the street, to do something special at a dance or come up with a running joke. These people were important to me.

The nicest stories about Belgrade were written by people from the provinces. Belgrade had always been a massive magnet for talented people, but what those born in Belgrade have written and have bound us with and what we're proud of because it is through them that we look forward to the success of those who came to Belgrade and made something amazing.

Sadly, once Belgrade used to be the target of the most talented people from our region. Today, it is the target of those we used to call 'swindlers', who'd come to Belgrade to show themselves through some reality show and make us think this is Belgrade. This isn't Belgrade.

You were born in Topcider, where you also grew up. You could say that your environment growing up was fairly unusual.

I was born in a Belgrade that had 400,000 residents. Now it has two million - meaning it's five times larger and five times different. The neighborhood above Milosev konak is the part of the city where I was born and raised. It was the end goal for anyone who wanted to make themselves big in former Yugoslavia - to make it to Dedinje.

Topcider was the place where we built our first court and church in Belgrade. This is where the first monument Zetelnica is located too, in the Topcider park. This was where Archibald Reiss lived. This was the location of the quarry that provided stone for some of the most important buildings in Belgrade, including my own school Branko Radicevic and 10th Belgrade Gimnazija and boarding house, today's archive. This stone was also used to build the base of the monument to Branko Radicevic in Strazilovo.

Don't forget that Milosev konak is located behind the last hill of Sumadija. It is where Sumadija ends and the flat lands towards Sava begin. This was where the Knjaz went into exile, from the pier near the Gospodarska mehana tavern and that was where he came back.

It's an interesting neighborhood. One of the first admitted students in that boarding house when it opened in 1936 was Nikola Karaklajic. Back then only the best students from Yugoslavia could come to this boarding school. Karaklajic was born in a cottage in Nebojsina street and he didn't remember his father, only his mother who washed dishes and laundry in their neighborhood. And he as a poor but gifted student went to school there and was in the same generation as king Peetar II. Together they were truly a prince and beggar.

When I was in junior and high school, I was classmates with kids of all the government officials of former Yugoslavia. From the families Broz and Rankovic to everyone else. They ate the same school lunch as we did, nobody went to private schools and they all grew up with us, went to same parties, celebrations and slava-days.

So you have fond memories of those days?

I was happy to go to a school that was surrounded by streets such as Petra Cajkovskog, Vase Pelagica and Andre Nikolica. None of them have been renamed. Imagine how wonderful it is to grow up in a school surrounded by streets bearing these great names, rather than a street that changes names every few years or so. That was my own happiness and that of my generation.

On the other hand, you grew up in a neighborhood where Hyde park is one of the biggest meeting places.

Thanks to your father, you've had the chance to meet some very significant people who left their trace in Belgrade while you were growing up.

It wasn't until I grew up that I realized how fascinating that part of my life truly was. In 1952 my father ran a furniture factory by the entrance to the Fairgrounds, where the Eurosalon used to be and is not a ruin. This factory was taken from him in 1946, so he got a work space for himself in Koste Glavinica street where he created all the studios in Belgrade including the first TV studio. He worked with the famous architects such as Mr. Dragisa Brasovan, our family friend.

In 1952 my father and Milovan Jaksic (the famous goalkeeper of our soccer representation from Montevideo in 1930), renewed the BASK club at the soccer club Senjak's court. I'm proud to say that the membership card number one was Milovan Jaksic, number 2 was Bogdan Popovic (my father), number 3 Vladanko Stojakovic, the famous sports coach and number 4 was me - three years old at the time.

I remember my father had donated the fence that was being built around the court. The fence was unfinished and when they played a game one week the fans were jumping up and down, making me fall into the plaster, out of which Milovan Jaksic saved me. He rescued me then and passed away three months later in Egypt, leading Red Star.

Your neighborhood was also very interesting.

The street I grew up in was constructed after WWI when king Petar I gave property on Topcider hill to the Belarus who brought culture in Serbia. Back then we had the Romanian street (today Uzicka), Tolstoy's street, Avgusta Senoje street which was mine (today it's Djoke Jovanovica street), Avgusta Cesarca and Teodora Drajzera.

Those were all homes of Russians, speakers at Radio Belgrade, architects...

The house I was born in belonged to the correspondent of the Russian "Pravda", Zukov, and it was constructed in 1924. But in 1948 after the Informbiro resolution he had to leave and ended up selling it to my father.

That's how I grew up among the Russian houses where all around me people spoke French and German. Across the street from me was a tall house built by Teodor Lukac, the father of the famous Sergei Lukac who founded journalism at the Faculty of Political Sciences and was one of the co-founders of NIN and a famous journalist.

Now imagine what it was like when his friends came over and he takes us kids to play soccer. Then Gligoric comes in, the famous chess player, to make his crew and Lukac invites us kids.

I also remember when a neighbor from my street, Mr. Ratko Petrovic, the director of GSP bought Lejland bus. His son Misa then brought a small model of Lejland to school to show us what the future buses of Belgrade would look like.

You could see Tito and Jovanka walking in the streets. It's not the same today. The president of Serbia lives 15m away from me, but you can't see him. If his car does fly by, it has darkened glass. Tito you could see walking around normally with no security.

Even shortly after Tito died, Pera Stambolic was the president for one term and he resided in our street too. He once dropped by our yard in slippers.

So you were always surrounded by great people and got to know them as regular people.

You know, back then we built the criteria of grandeur based on our heroes from books and movies. My heroes were Tom Sawyer, Ivanhoe, Odysseus, Ava Gardner, Frank Sinatra, Elvis - because they did something great.

When I was 13, my heroes were the Beatles because they conquered the entire world without firing a single gunshot. They showed that in the 20th century, the time of great wars, conflict and hatred, it was possible to take over the world without a single shot fired.

Later came Michael Jordan, Cassius Clay, Michael Jackson...you know in America those were the days when Jordan and Chicago got their sixth title. A man said to me that there isn't a single person on the globe who wouldn't rush out to see Michael Jordan if he walked down their street.

And today we admire some other aspects of people, instead of asking them "Excuse me, what have you done that's so great?" Let our heroes today go to Sudan or Tasmania and be recognized instantly.

We didn't care about people in politics. Politics entered our lives far too late and didn't matter to us. How do you idolize someone whose son or daughter you know personally as normal people. Those kids didn't ask for preferable treatment in school, nobody picked them up or dropped them off in cars - they hanged out with us during recess and ate the same slice of bread with yellow cheese.

From the time I grew up came at least 10 famous journalists, but Ivana Zivkov, the daughter of Pera Stambolic, was the best writer of us all. And then there were Tirke and Borka Pavicevic, Nenad Briski, Moma Pantelic, Branka Jeremic, Bojana Antunovic, Macan Vesovic, Vlada Bajac...all of them ended up editors of big newspapers.

I'm proud of the fact that I know that there was a time when you didn't matter because of your parents' names, but because you were good at what you did. Don't forget that in our neighborhood they also founded a rock band consisting completely of politicians' kids. They came to Nikola Karaklajic to ask him what they should name their band and he told them that the best name for them would be 'Bravo', because nobody would yell 'Boo Bravo'.

I remember going to the first 'Gitarijada' festival in 1966 and we all went together. You have 101 images from Gitarijada by Tomislav Peternik and professor Debeljkovic and in 20 or so of them you can see executives' kids jumping with us, as well as Dobrica Cosic watching what's going on and Makavejev. Make a concert today and put a politician in the fan pit.

It was a different time then.

Everyone shared everything together.

I had relatives in Canada and Scotland. When they send over a package of chewing gum I'd take it to school and share with everyone. That's how we all grew up, sharing with each other, regardless of who came from where. It's something that later conditioned you in life to realize that many things are passing but kindness and friendship stay forever.

And memory.

I'm not a writer myself, but I remember some things and don't let myself forget. I don't let anyone come and say 'they're all the same'. They aren't. Because they didn't all enter public transportation with the same ambitions. Some wanted to become rich, but I was always impressed by those who wanted to do something good, mostly for the city. To do something never done before and say 'That's Belgrade'.

So Belgrade was the city that educated you in a certain way?

Since my mom gave birth to me and up until this day, anything I did I did for free if it was for Belgrade. I didn't want to take a dime from the city for what it taught me in the first place.

Let's say in 1966 right there in the city tavern in Republic square Miljan Miljanic would sit every afternoon talking with us. We come over and ask him what he thought of our friend Jaksa's game and he says "Oh, he's got a good right leg but he's not taking it seriously."

And then in Terazije you have Jovan Bulj who's guiding the traffic and near the 'Horse' in the evening we meet our friends from Zagreb. Kina and Sima come on their motorbikes in the afternoon and we go to Laza Secer's disco and then they have to go back to Zagreb in 1AM because they play ballet.

Magic buses that ran between Lundon and Istanbul would stop in Republic square and Marks and Engels square. Then you meet new people, take them home, get to know them.

You see Ivo Andric going down Knez Mihajlova towards little Kalemegdan to watch basketball and across the way from the Russian emperor is Zucko. You can take one stroll and see entire Belgrade out and about.

It was just that kind of time.

Mind you, when Beatles sang 'All you need is love' in Mondovision in 1967, the very next day outside the Dom omladine we were already all wearing floral pattern shirts we took from our moms and aunts.

And there was no internet. You listened to Radio Luxemburg which came in grainy and tomorrow you come to school and lie about what you heard because nobody knew English. Then in Gitarijada the singers would come out to sing songs in English with the lyrics phonetically written on their arms.

For example, when the first Fest was held, they showed Woodstock and Easy riders. In the hall of the Dom sindikata, you saw a man who everyone said would be a famous actor - Jack Nicholson and anyone could approach him and talk.

It was there that I recognized Peter Fonda and his girlfriend who was Michel from Mammas and Pappas and next to them was Denis Hoper, the hero of the movie Easy riders. And this was all normal to us.

Then you had the book fair starting at 1957. I was in second grade of junior school and our teacher Jovanka Kalaban took us there and ever since then I've attended every book fair to date.

I would bring in under my arm books that cost what today equated to 3 dinars and later in life meant a lot to me.

I found the bedeker of Milos Crnjanski about Belgrade from 1936. Now it's published as a luxury edition and back then it was a modest little booklet any traveler could get in Belgrade so they could learn about the city.

I remember that Politika, back in its day, would publish an amazing 800 new editions at the Book fair, when now there are over 12.000 every year.

On the other hand, there were also some - let's say unconventional teachers.

When you talk about Belgrade, I talk about Tofia, the most famous broad of my generation at the time when there were no reality shows.

There is a documentary movie called "Brick for a teacher". It isn't about Tofia, our friend, but it's a similar example. It's about an elderly Romani woman who lived in Banat in a rundown house. The movie is about her and how she taught people when she was young and healthy and back then her house was beautiful and neat, but over time it all fell apart. Then every student she'd ever taught brought a single brick and they built her a new house.

That was Tofija in our day. People would be sitting in "Sibica", a tavern belonging to the "Graficar" club and she'd come over and just point and say "I was with that guy and that guy and that one..." and they would immediately flee from the tavern.

She was one of those personalities from the late 60's who was a teacher. Nobody got any diseases from her and Tofija was the symbol of Belgrade.

What would you change about Belgrade today?

If I had the authority, I'd make the decision that the mayor of Belgrade has to be born in Belgrade and the same would go for any other city. Why?

The problem is when there isn't some granny or grandpa who will ask you "Say, sonny, what are you making of this city of ours?"

If you are from Belgrade, you have a responsibility to your childhood, the streets where you grew up, your neighborhood and values. I saw the sky, the grass, the rivers for the first time in this city - that's an obligation.

That's why in the world there are cities where you can't be the mayor unless you were born there. That person has to know what needs to be protected and preserve the culture of the city.

You have a very diverse career. Rock historian, journalist, you've filmed a documentary about Sreten Stefanovic, the Olympian, titled "Life as a collection of circles". You've also worked abroad. What guided you in your work.

When you do something in your city you have an obligation not to embarrass yourself and when you work abroad then you carry with you the spirit of this city. I always loved being involved in things that other people haven't done before. Because there's no point in repeating something others have done better already. But to participate in some small advancements, that was always a challenge for me, just like working with new people and leading younger generations.

My idols were the ones who gave me my opportunities. Nikola Karaklajic, Dusko Radovic, Mica Ilic Minimaks, Dragan Markovic Tirke, Milan Vlajcic, the best people in the business called me. In those situations, you have an obligation to do a good job.

Money doesn't matter in life, what matters to me is to not embarrass myself and squander the trust that someone has shown you. Once you fail their expectations, it's for life.

My other principle was to never do what I love for money. I was fortunate to have a stable income in my workplace. However, that income was managed by my wife so I never really knew what I was getting paid.

I didn't want to take any money for anything else I did because I was already paid. How can you pay me when I'm an editor for a newspaper? How can you pay me if I work for the UN or the EU?

If you tell me I work for one or one hundred dinars, then I have a price-tag and can be blackmailed by it. If you work for free, that's the costliest for everyone involved. To you because if you embarrass yourself the entire system fails and if you do well you'll encourage someone near you to work and see that as a possibility.

I always liked bringing together people you can see light up the night, like there's something shining from inside of them. On the radio I was given a chance even though there was a committee of speakers who wrote on the board that I wasn't allowed to go live on program because I can't say the letter "R" and Nikola Karaklajic let me speak anyway.

I had never participated in a labor action so I went as brigade commander and we were the best in Yugoslavia. My only condition was to have people who also never went to a labor action. Because those who have, they've been spoiled - they already knew how to fake it.

I was the only commander with 18 calluses. I couldn't straighten my fingers for months. But how could I be a commander while I sit in the shade and everyone else worked. How do we dig sewage through a septic tank if I wasn't going first?

Those were my principles, that's the only way you can set an example.

One of your greatest successes was with your "Rock" magazine

I was fortunate to print the largest publication with my crew which started in the basement of Politika to produce 150.000 sold copies.

We were in the old building located between Sumatovac and the new Politika building. When we got together I told them "This building is inhabited by ghosts. These same offices were once used by Nusic, Crnjanski, Andric, Ribinkari. All the most famous authors of our language and we have to defend that spirit." People who left that editorial office won all the awards in the world.

Rasic is a photographer in London, Tanja is working for a radio station in Australia, Vejvoda does movies and music in Paris, Snezana worked with Marina Abramovic and now she's an artist in Germany, Markovic is now an editor for the Cosmopoliten in Spain - all of them came from this same editorial office.

Today there isn't such a thing as youth publications anymore so there's no way to pull from that kind of pull. Someone just plugs in through Twitter or Facebook and becomes a journalist just like that.

It's not like back in the day when every day you could see Vibo or Mr. Predrag Milojevic in person. When you saw them it left an impression on you - they were giants of their time. I was fortunate and privileged to know all the giants I ever wanted to meet and learn from them.

Now your book is coming out.

It's called "Springs in Topcider". As of 2007 I've written for Blic every week and there are over 700 texts there. Out of those, 173 have been about Belgrade in one way or another and then Mihajlo Pantic, the editor of Knjizevna opstina Vrsac, asked me if he could make a selection and publish it. That's how they selected 59 texts and made them into a book.

You own a very important archive of magazines and literature related to rock music. What do you plan to do with it?

There are two initiatives - one private where musicians are trying to revive the Rock museum and the other by the Museum of Yugoslavia. I'm leaning towards gifting my collection to the Museum of Yugoslavia because I was born in Yugoslavia and what I did was linked to the space of language and emotions.

Sadly, a lot of its legacy was lost over the years. For example, in 1985 in Zajecar's Gitarijada, the Rock magazine was one of the endorsers and they asked me what they could do as a follow-up event. I suggested they should have an exhibit of our earliest music magazines in their library. I sent them 64 magazines to use and after the event was over they were tossed into the Timok river. If I had them now, they would've been worth at least 200.000 dollars. There was the first edition of Bilboard from 1896, the first edition of Melody maker from 1926, the first edition of New musical from 1952, the first edition of Sounds from 1970 which was the test edition and the first edition of the Rolling Stone magazine of which only 8000 copies were ever sold. All of them were thrown away.

Our people still don't understand the immense value of these types of thing.

You've met many stars and interviewed them. Who left the biggest impression on you?

I think my most precious experience was David Byrne from Talking heads. We met in 1982. He was born in the small-town Dumbarton in Scotland where I also lived for four years.

Between 1977 and 2019 he's been popular the entire time but never by relying on the past. He'd always be up with the times, always finding something new.

When he came to Belgrade the first time in 1982 I asked him if I could get him anything. He said "Records with your national folk music". He took over 27 albums with me and later sent me a postcard that said 'Wow there are interesting records".

What are Peca Popovic's plans for the future.

When you have health like mine, you can't plan too far ahead. I have 13 stents, 8 bypasses, 8 surgeries, 7 heart-attacks. You have to endure all of that. There's still work I need to finish. I'm waiting on my grandkid, that's my current challenge.

Everything I'm agreeing to now is for very short periods of time. I can't tell anyone I'll be there in a year, it's not okay. It would be irresponsible - how do I make a commitment, then let you down.

Stil, even after so many years of work you are still full of energy.

What else can you do? You're a pensioner so you should give up? Go play chess and have someone take your knight or pawn?

I think I just still have obligations. There are so many little things to do still. There are more talents to encourage, ideas to help and it's a shame not to.

I can't do anything grand, but I think my experience can help those who would like to do something. It's important to encourage your talent. I believe that talent deserves to be shown and an idea deserves to be realized if it's good.

Right now I'm busy with the ethno-archeological-ecological region of Zup. In this region out of 39km2 there are two types of autochthone iron - Tamnjanik and Rskavac (Prokupac) which St. Sava brought from his father's grave in Hilandar.

This was where the inventor of vinjak, Mr. Markovic used to live. Vinjak is a portmanteau of the words whiskey and cognac. After being wounded in WWI he graduated in enology in France and brought that idea to Serbia.

What we're trying to do is revive an area above Zupa which now mostly consists of 'field houses' where people lived from St. Trifun's day to the harvest, picking grapes. We want to make an ethnic village, library and museum of the area there, make the houses like hotels and have everything protected by UNESCO.

I believe this should be done, though it's very complicated. There are luckily some young people too who want to see it through.

6 ℃

6 ℃