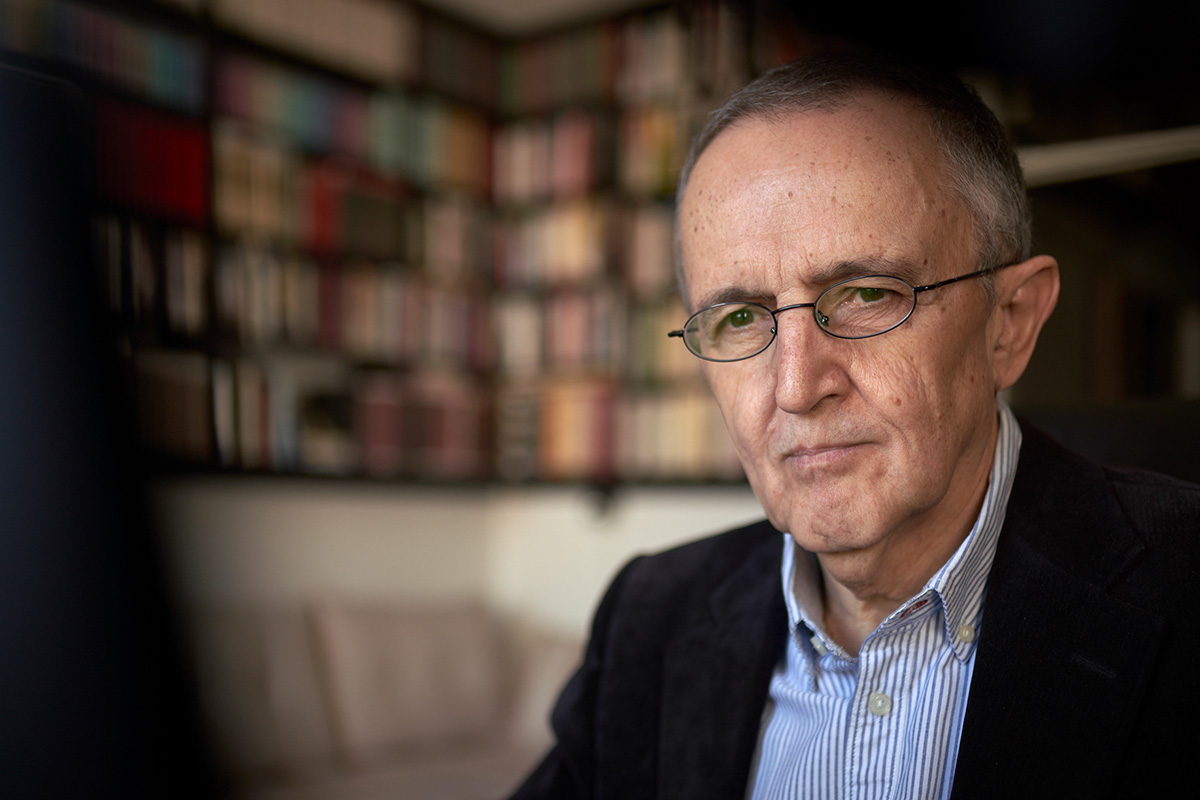

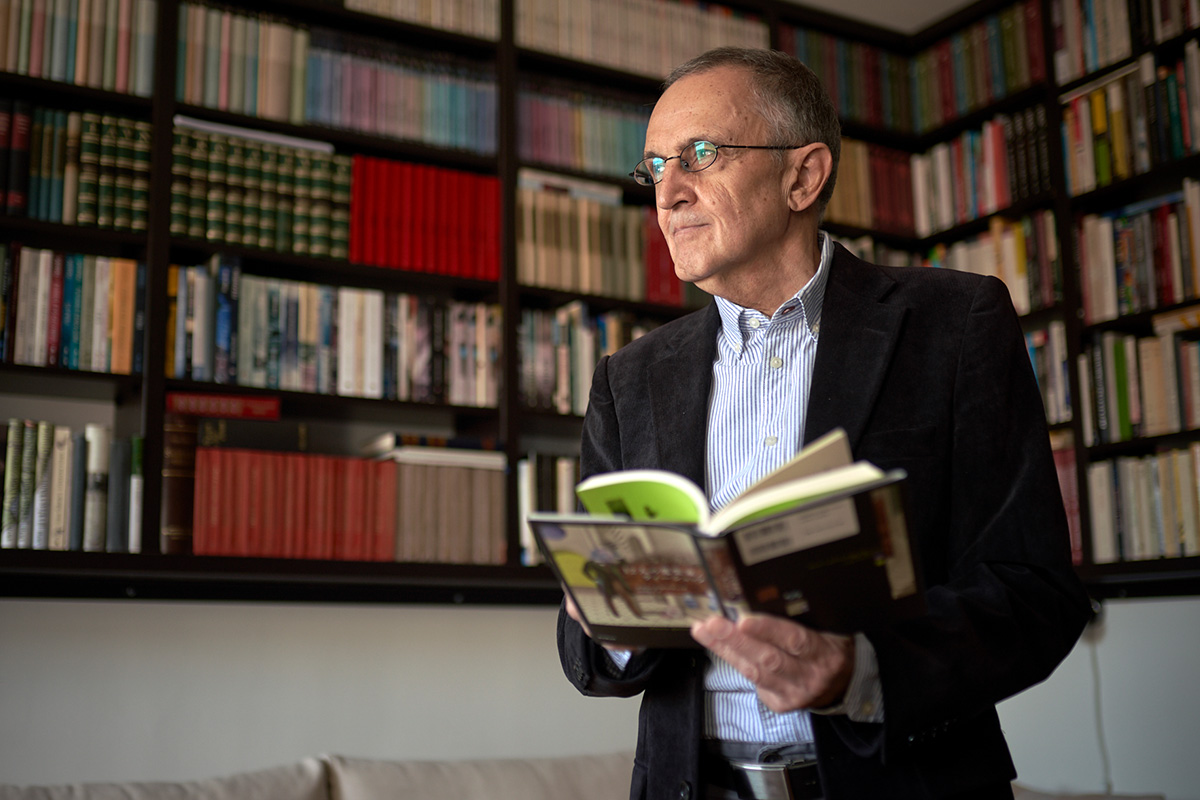

Zoran Zivkovic: the Belgrader whose books are read throughout the world

Professor Zoran Zivkovic is one of our most-translated and most-popular authors. His rich experience and sophisticated style gave birth to twenty-two books, and his vivid storytelling seamlessly pull the reader into the plot and make them want to read every book in a single sitting.

You were born shortly after WWII ended. How do you remember the Belgrade of your childhood?

As a place without too much traffic, with lots of fresh air, horse carriages, heavy winter snowfall, 1st of May parades, long queues at cinemas, the unique barbecue scent around the “Lipov lad” tavern, swimming in Ada, playing soccer in the street, Djordje Marjanovic’s concerts...but above all I remember it for a little girlie with bangs and a bow in her hair, the one with a button nose that smiled at me one time for some reason.

From today’s perspective, we see those times as the ‘good old times’, remembering them with nostalgia. Do you also remember it as something you miss or are there other emotions in play?

It’s not about “the good old times”, it’s about the “old good youth”. The one that, as the song-writer says, gave and stole away, was not loyal and didn’t give too much...

What was it like to grow up in Belgrade in the 60’s and 70’s of the past century? How did young people enjoy leisure? What was their nightlife like?

In the 60’s we listened to vinyl records, national more than international artists. We listened to Radio Luxemburg, the first rock ‘n’ roll bands showed up, we went to dances. The Twist was a popular dance for a time, then the Beatles exploded and nothing was the same anymore. We had entered the modern days.

In the 70’s I was already an adult: I’d graduated from college, got married, got my magistrate, the twins were on the way. In short, the time for sports and leisure was gone.

Compared to today’s social mindset, including the internet, mobile phones and the like, would you say that time was better or worse?

I’d say neither. It was different. My students can still just barely imagine the world without the internet. They imagine us poor souls who had to live in that time almost as cave-people, but they can still imagine it. Imagining life without cellphones, however, is a different story. Imagination fails them completely in that regard. No matter how I try to assure them we lived just fine and well without cellphones – maybe less conveniently, but at least we didn’t have to listen to private or even intimate conversations in public transportation while everyone keep staring at their screens without noticing the world around them.

What was the student life like at the time when you were in college? Movies and shows that depict those years usually give us a romanticized version.

That time is something that changed the least with the generations. The auditoriums of the Philology college that I attended are no different to those where I came to teach 35 years later. If there weren’t for the cellphones and slightly different fashion sense, I could almost imagine in 2007 that I was back in 1968.

What did you think of the student protests in 1968? Were the students, as Tito finally confessed, right all along? What consequences did you feel after the protest?

I didn’t cross paths with the student protests in 1968. They happened in the spring and I became a student in the fall. In addition, politics didn’t really interest me as much as it would in the 90’s.

Can you draw any parallels with the later student protests in 1992 and 1996?

Without a doubt yes, but by that point I was no longer a student so I’m probably not the right person to ask. I spent that decade in the streets and squares, protesting until exhaustion as an adult who maybe didn’t know yet what he wanted, but he definitely knew what – or whom – he didn’t want...

You are one of our most translated authors among the modern Serbian writers. Your stories were even broadcast on BBC radio, you have won many awards... what was the secret of that success? Was it that you began writing dedicatedly at 45 or maybe the love of writing and reading or something entirely else?

No matter what answer I give it will sound like bragging, which is a practice I despise the most. Maybe the least prideful thing I can say is that what I write isn’t bad, because if it were, it wouldn’t have gone to so many countries. A writer can maybe trick one or two publishers, but not more than 50.

How did you end up in the world of science fiction? What is it that sci-fi gives to you as an author on the one hand and the readers and fans on the other?

Before anything else, I wouldn’t call myself a science fiction author. Despite the popular misconception, especially among those who for reasons justified or not didn’t get to read any of my 22 prose works, there is no sci-fi in them, even in traces. I did work in science fiction for about 15 years between 1975 and 1990 in various different ways: I was a translator, editor, publisher, historian and genre theoretic, I based my magistrate and doctorate on it, I wrote the “Sci-fi encyclopedia”. The only thing I never did in that field was writing. I couldn’t have because I wrote my first line of prose in 1993, when I was well out of the sci-fi sphere.

How do you find inspiration for your books? Do you see writing itself as a certain trade that has to be learned and practiced, or is it a sense of art that you are either born with or not?

If it were just a trade then anyone could learn to write good books. However, seeing how there are far more poor than good works of literature in the world, it’s obviously a matter of art. As far as inspiration goes, if I ever manage to figure it out, it will be my greatest literary accomplishment, and not just as an author.

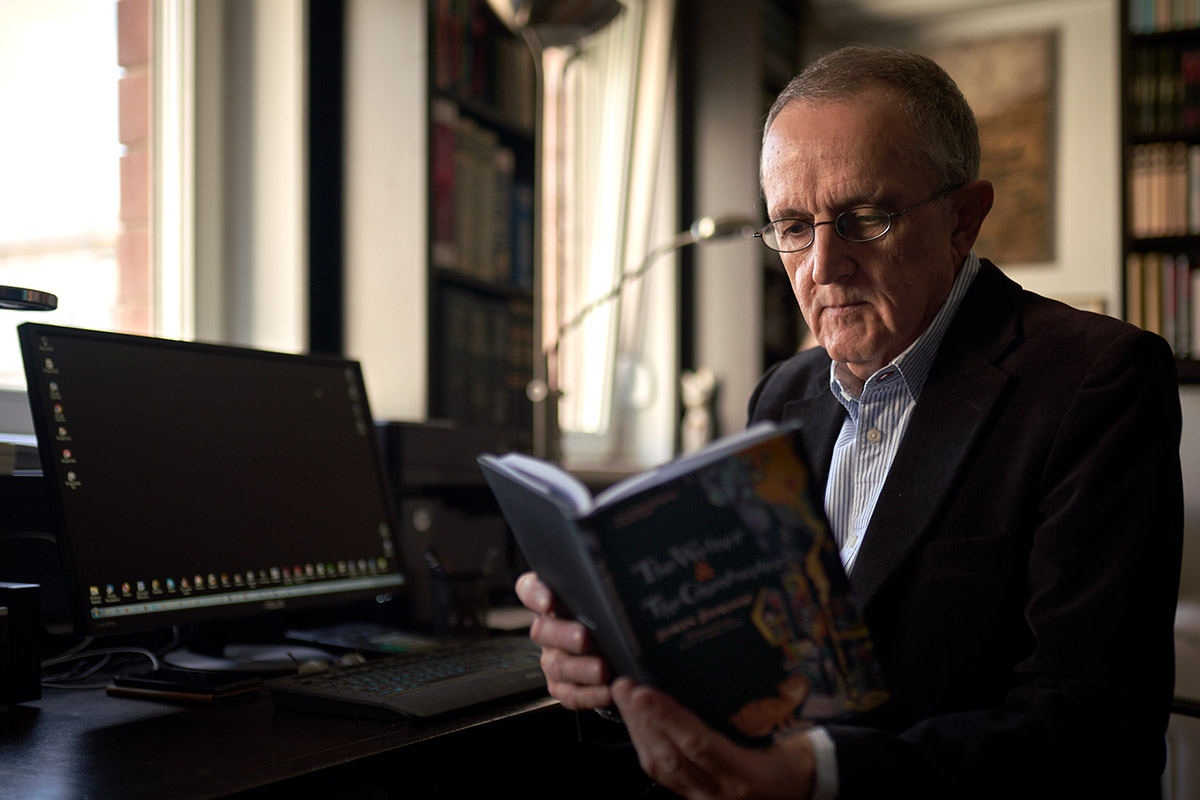

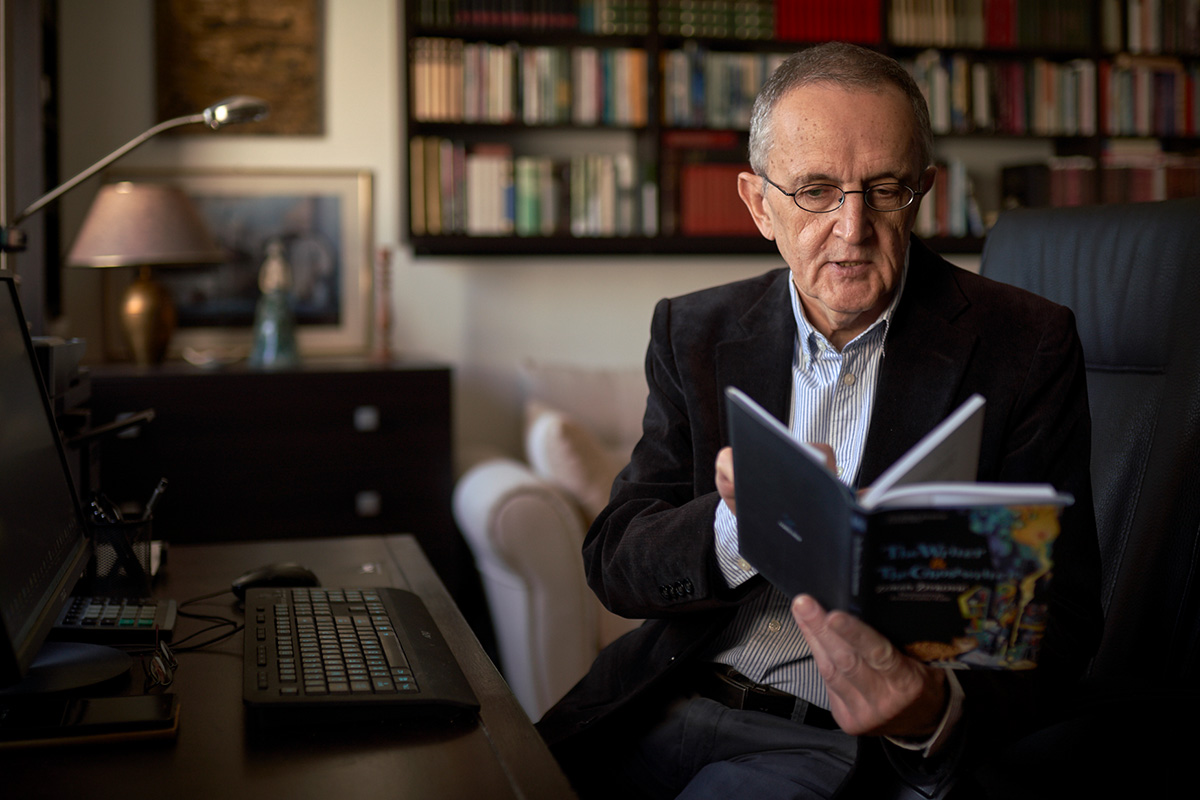

Do you have certain rituals when you work? Is there an element of superstition, to put it that way?

I am not a man of superstition. If anything, I am a man of skepticism. When a work has ‘ripened’ inside of my head, I simply sit down and start writing. There’s no mysticism involved or any reason for superstitious rituals.

What would you highlight from your past work and for what reason?

I am probably the only person on the planet that shouldn’t answer that question. As a writer, I’m not supposed to have favorite works, at least not officially. As for unofficially – well, my lips are sealed there.

The courses of creative writing you do draw a lot of attention. What do you get out of that line of work? Do you find any talented future writers?

Working with the students in my courses gives me the precious pleasure to be able to provide mentorship and support to budding writers who benefit greatly from this type of guidance. They would’ve probably reached the same conclusion I teach in time, but this way I believe makes it easier and simpler for them. The real treat as you said comes from running into those rare truly gifted people who only need a bit of guidance and advice. Still, let’s be clear – I can’t make someone a writer if they already aren’t at least to some extent. If they don’t have their unique ‘prose voice’. But, I can certainly facilitate years of studying which is not negligible.

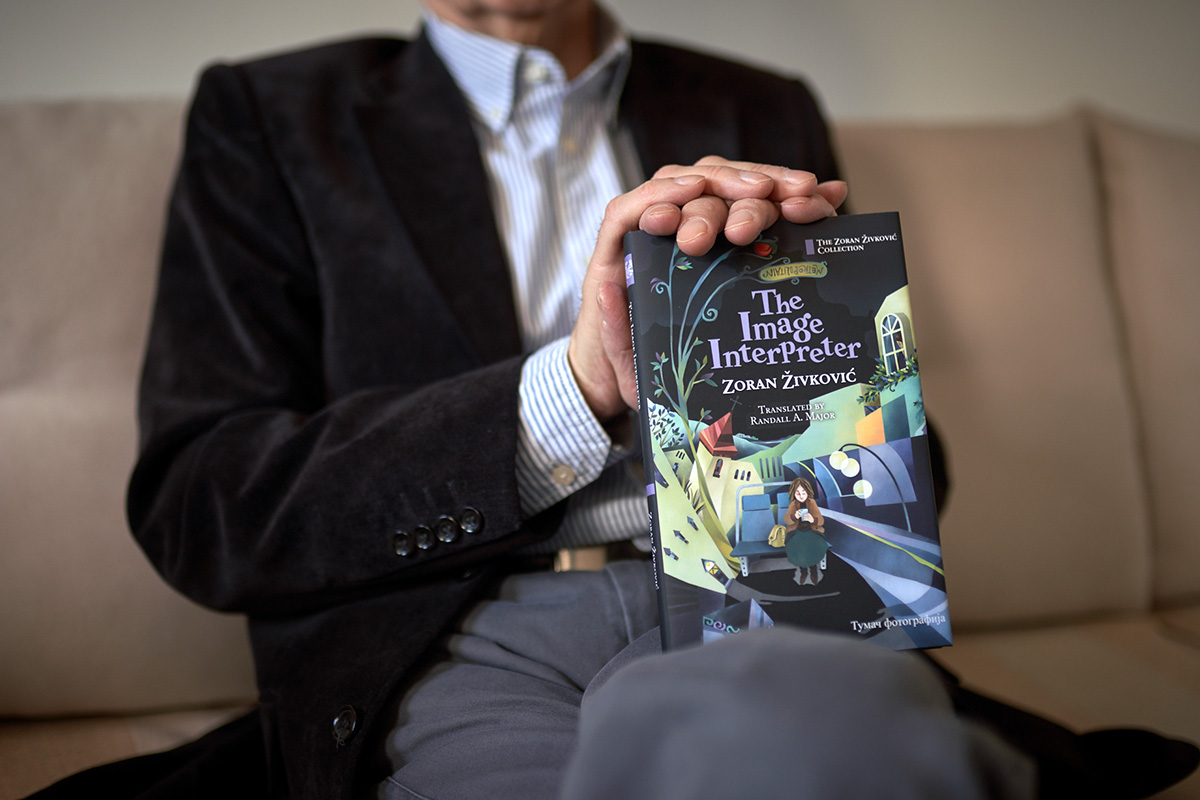

Is it possible to make a living writing in Serbia? Judging by your novel “The Image Interpreter” which is a great hit in the world but didn’t really catch the public eye here, it seems like the answer is clear.

It’s not possible make a living in Serbia writing artistic prose. It is however quite possible to make a comfortable living writing trivial literature. Sky is the limit there. It’s just like music – when have you heard of a Serbian artistic composer who lives off his work, while turbo-folk divas lavishly enjoy the fruits of their howling...

When it comes to prose, the reverse rule applies: it’s easiest to be a prophet in your own village. Many local writers have never left their village – they find it quite comfortable there. Everyone knows them, everyone respects them, this is where they get awards and recognition. Why should they bother going out into the world?

When it comes to myself, I never really wanted to be a prophet of any kind – in my village, in my city or in the world. I never wrote with the ambition of prophesying anything either literally or metaphorically.

Is it a ‘shameful offer’ to become a ‘writer for hire’, which is one of the legitimate ways for a writer to survive nowadays?

I wouldn’t know. I never got such an offer. I’d like to say I wouldn’t agree to one if it ever came, but I know it’s easy to champion morality when you are not the one being tempted.

What are you currently working on and what are your plans for the future – both involving new books as well as your creative writing school.

If you’ve already written 22 books and you are not chasing glory, then it’s inevitable to wonder is there a point to writing the 23rd? What is there that you haven’t already said that requires a new novel? Already at the start of my course of creative writing, I give my students the first hard-to-swallow truth about the art they’ve chosen to work in – you should know when to stop. Avoid disgracing your career with weak and unnecessary works just to maintain this illusion that you still live as a writer. It’s always better to publish nothing, rather than to put out something of poor quality, which will be the rotten apple that spoils the entire basket of the fruits of your labor known as your ‘opus’.

In short, I am currently not working on a new book – I have plenty of old ones for those who wish to read my work. My plans are related more to the past than the future. One thing is for certain – I will continue to work in creative writing. On that field I definitely have more to say and there is no danger there like the rotten apple I mentioned before. On the contrary – everything is fresh and ripe as can be...

6 ℃

6 ℃