Photo: Arhiva NBS

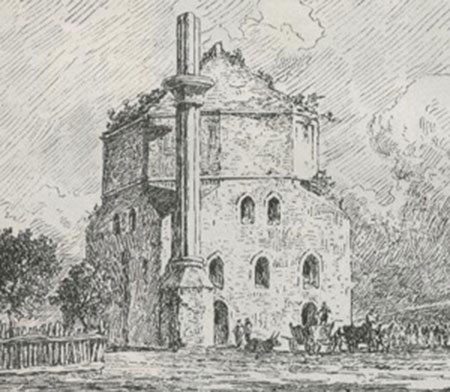

Batal mosque - the former Hagia Sophia of Belgrade

Imagine yourself walking through the “Darol jihad” – the house of wars as the Turks used to call Belgrade in the days of the Ottoman Empire. One foot after the other, you’re on your way to Tasmajdan. You glance in the direction where the National Assembly is located today and, instead of a political, you spot a religious temple. And not just any temple. It was the “Batal” mosque in all its glory – at the time the largest and most beautiful construction in Serbia, back then rivaled only – according to the travelling writers of that day – by the famous Hagia Sophia.

The Batal mosque was damaged frequently in many battles before finally being torn down in 1878 by decree of Prince Milos Obrenovic who refused all pleas from Constantinople to renovate it. Only a few years later, the grandiose National Assembly building was erected in that same spot.

Drawing:Konstantin Jovanovic

Constructed in a strategic position

The Batal mosque was constructed by the wealthy Belgrade official Ejnehan-beg in 1585 who named it after himself, which was the name it held until 1789.

The location of the mosque was carefully selected to be on the edge of the city, in what would future wars prove was a strategic position for city defense. This is confirmed by an Austrian report from the end of the 18 century where it is precisely stated that the mosque was “1000 steps away from that city rampart which surrounded the settlement”.

Batal mosque inspired admiration with its appearance. It was constructed from carved sandstones which in time became reddish-gray. It was 18m tall while the side walls were 15m, and the interior was illuminated by 20 windows that ended in pointed arches.

The interior was set on the North side while the “minaret” was constructed on a pedestal which had eight sides. Inside, the walls were lavishly decorated and the niches under the arch were decorated in the form of stalactite. Above the “mihrab” there were decorative arches made out of interchanging light and dark blocks.

Next to the mosque there was a graveyard where influential Turks were laid to rest. From its “minaret” the faithful were called to prayer and the object itself was the main Turkish prayer site out of 11 other mosques in Belgrade.

In the beginning, the Turks constructed slaughter houses on the left side of the mosque where they slaughtered rams, skinned them and melted their fat. This was done because the mosque was located on the border of the city so the people weren’t bothered by the smell.

On many occasions the mosque was torn down and repaired. It wasn’t until 1766 that was repaired for the first time, only to be badly damaged again in 1789. This is when it got its name Batal mosque, which in Turkish means “neglected”.

On the front line

The first time that the mosque was damaged, it happened in the Austrian attack on Belgrade in 1717, under the leadership of Eugene Savoy. During the second Austrian occupation of Belgrade (1717 – 1739) it was turned into a uniform warehouse for the Prince Alexander of Wurttemberg’s regiment.

However, soon after the Turks defeated the Austrian army at Grocka in 1739 and came back to Belgrade to begin the reconstruction. The work was finished in 1766 and around 7000 groat was spent for this purpose.

Graphics: Joh. David, Ben Kenckel - Battle at Belgrade 1717.

The mosque didn’t get to keep its glow for long.

It was damaged once again in the battles for Belgrade in 1789. The Turks used it for defense and the head commander of the Austrian troups, Marshall Laudon was the one who directed the points of attack on Belgrade. At that point the Austrians took over Belgrade from the Turks, but only got to keep it for two years.

The misfortunes of Batal mosque weren’t over, however. During the battles for the liberation of Belgrade in the First Serbian Uprising in 1806, the Turks used the building to provide strong resistance to the rebels who were stationed in the territory of Tasmajdan. In these battles, the mosque was badly damaged when Karadjordje’s artillery struck it from the cherry cannon and split the minaret in half.

During the period of the Second Serbian Uprising, the rebels set up guard in the mosque and used it to control the Danube side of Belgrade and the Vidin gate.

The futile pleas from Constantinople

The Belgrade vizier, Jusuf-pasha, had the intention of fixing the mosque when the battles were over. He notified Prince Milos of his intent on the 20th June 1836. He then wrote to him that “...the engineer Ethem-bej saw cattle entering the mosque, which is why he constructed the door for it...”

Pasha explained in vain that 50,000 groats were sent to him, two golden half-moons of alem and a feman which orders him to repair Batal mosque. That “...our Emperor...has a great desire to restore foundations” and pointed out that “repairs should be done so that the nizami who would be practicing in Vracar when the time is come could pray in the mosque”.

Prince Milos was hard-hearted in this regard. He refused the renovation with the explanation that this part was in Serbian hands and near the Palilula church. The pleas from Constantinople were also futile because Princ Milos considered that restoring Batal mosque would mean spreading the Turkish rule outside the borders of Belgrade municipality, which by the edict which decreed all land outside the municipality to belong to Serbia, was not allowed.

Milos even commanded that the ground was dug through and tiled and that more police force is distributed around Batal mosque, in order to make sure that the Turkish army would not return. Milos ordered that the Savamala was burned down and that any disobedient Savamalians were relocated around Batal mosque where there was also a cattle market.

Photo: Pavle Kaplanec

Torn down for a handful of gold coins

When Karadjordje conquered Belgrade, the serefs and the top of the minaret were already torn down, but the central part of the mosque still defied time. The then director of the Library Janko Safarik had the idea to turn the Batal mosque into a Serbian National Museum and Prince Mihailo wanted to repair it and store the National archives in it.

K.N. Hristic wrote about the state of the building: “The interior of the mosque was a dumping ground for the entire area, full of all sorts of filth. The main entrance was on the building’s North side, facing the town, but all the windows on it were damaged nearly to the ground, so it looked like it was standing on its arches. The top of the minaret was damaged...birds like sparrows and crows made nests and bred in the cracks of the walls in thousands and in the night swarms of bats would circle it. The roof, covered in dirt and dust for years, was covered in spiky weeds. The cracks even gave home to a black mulberry tree which was always full of sparrows whose chirping could drive one insane.”

In the end, soon after the Ottomans left in 1867, the old Batal mosque was finally torn down in 1869 or 1878 by the order of Blaznavac, a town official. The deconstruction was done by Cincars for 230 gold coins paid by a cafe owner called Pandjalo.

This was the end of Belgrade’s Hagia Sophia.

7 ℃

7 ℃