Photo: Igor Spasic / Flickr

The biography of a Victor

He has the best view in the city, greets ships and overlooks the joining of Sava and Danube. He’s proud and over a century old. Above all, he is the symbol of Belgrade. It’s not well-known that in its day the monument to the Victor has caused more anger and debate than the unfortunate fountain in Slavija today.

Who did ‘the Victor’ win against?

In 1913 the leadership in Belgrade decided that it was time that the city gets a monument to celebrate the end of I Balkan War (and then the II as well). Ivan Mestrovic who was by then already a renowned sculptor in our country and the world took on this very important assignment.

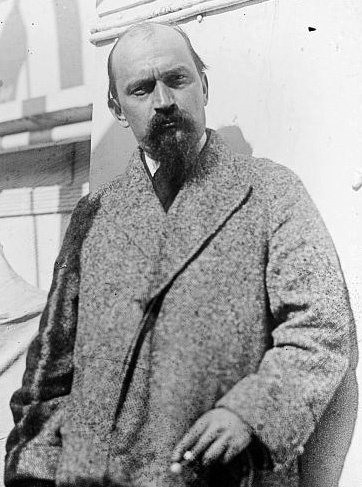

Foto: George Grantham Bain Collection

Foto: George Grantham Bain Collection

The first shapes of the bronze body that will become the symbol of Belgrade were born in the gym hall of “Kralj Petar I” junior school, in the street which today has the same name. Notes say that for the needs of making a 5m tall monument which surpassed the capacity of most closed spaces in Belgrade, the top of the gym hall was removed so the Victor stretched up two stories. Mestrovic’s idea was in agreement with the city management and it involved placing the monument in Terazije which, back in the day were like the Square of crown prince Alexander on top of the large oval fountain. The project was called Allegory.

Already next year the WWI began and Mestrovic was forced to leave his studio in Belgrade and went to Prague. His unfinished work was stashed in a basement in Senjak where it would remain hidden for the next several years. In addition to the Victor, Mestrovic also worked on molds for a beautiful fountain. The central column that stretched on five ‘stories’ that represented five hundred years under the Turkish rule as supposed to be surrounded by lions that greeted the war and were destroyed by it in the basement of the school where the sculptor worked.

Foto: Arhiva Narodne biblioteke Srbije

Foto: Arhiva Narodne biblioteke Srbije

Nudity is just for the curious

When peace returned and the artist was ready to continue where he’d left off, new circumstances in the country were such that people were no longer interested in the monument. Furthermore, the city council refused to pay Mestrovic for his work thus far and so began a long process of trials and press wars of that time. There were even stories that the ladies of Belgrade opposed public nudity so the idea of a fully nude, artificial man in the middle of the square was unacceptable to them. In reality, it was the men who were behind this notion, seeing how they were the only ones who played a part in Serbia’s political scene at that time. Individuals accepted the monument, but insisted that it was placed in a different location, such as today’s Republic square. A third group felt that there was nothing problematic about the monument at all. We can’t even imagine how the voice of the people would manifest on Facebook, if it had existed in the 1910. There was press, however, and journalist jumped at the chance to express their own opinions – as much as they dared – through irony and satire. They suggested that the monument be placed in a different location every week, or that it’s placed in Terazije and then dressed depending on the weather conditions. Or, to put it inside the fountain so that at least it would have an excuse for being nude (we probably all agree that this was the most original idea).

Foto: Arhiva Narodne biblioteke Srbije

Foto: Arhiva Narodne biblioteke Srbije

Either way, in 1928 – around 15 years late – the city finally made the decision. The monument will, without its fountain, take its place in Kalemegdan overpass, facing the rivers, so that its most intimate parts can only be witnessed by those who really try. And so it was – on the anniversary of the breach in Solun front, on top of a 12m tall pillar, the Victor took his stand.

A fearsome warrior with a determined expression, a Slav Hercules with a downcast, but ready sword in his right and a gray hawk on his left hand, became the guardian of the city and celebrated the victory of all Yugoslavians over their enemies. The fountain, whose pieces disappeared or were destroyed, came to life in the hands of the sculptor Veselko Zoric, based on Mestrovic’s designs that were discovered in his atelier in Zagreb.

The attack on the Victor never ceased, however. Moreover, forums and comment sections of articles about him are wrought with discussions and even arguments, mostly driven by nationalistic beliefs. They range in topic from the ambivalence of the Victor’s symbols, alleged hidden intents of the artist to his true nationality. This makes us wonder – if there wasn’t for the Victor, what would’ve been the symbol of Belgrade?

6 ℃

6 ℃